Imagine you're a physician in the 18th century, observing that patients who receive a particular treatment tend to recover. You notice this pattern again and again, treatment and recovery seem to go hand in hand. Your mind begins to form an expectation: when I see treatment, I expect to see recovery.

This is precisely what the Scottish philosopher David Hume observed about human understanding. In his groundbreaking work, Hume argued that our belief in causation is fundamentally built on three pillars:

But here's the revolutionary insight that shook philosophy to its core: We can never directly observe causation itself. We only observe patterns, associations, correlations. The "feeling of expectation" that makes us believe in causation is, in Hume's view, a psychological habit, not a logical certainty.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and this philosophical puzzle has become a practical crisis in medicine, public policy, and data science. We have more data than ever before, but distinguishing true causes from mere correlations remains one of the most challenging problems in science.

Consider a scenario that plays out in hospitals and research labs every day:

A new drug is developed to treat a disease.

Early observations show that patients who receive better the drug have better recovery rates than those who don’t.

The correlation is strong, the statistical significance is clear. The drug appears to work.

But here's the catch:

What if patients with a certain genetic predisposition are both more likely to receive the drug (perhaps because their doctors recognise they're good candidates) and more likely to recover (because of their genetics)?

In this case, the drug might not be causing recovery at all—it might just be correlated with recovery through a hidden third factor: genetics.

Let's bring this abstract problem to life with a concrete example. We'll simulate a clinical scenario where:

The critical question we need to answer:

Does the drug actually cause recovery, or is the association we observe merely a mirage created by genetic predisposition?

In reality, we would never know the true data-generating process. But for demonstration purposes, we'll simulate data where we know the truth: the drug does have a real causal effect, but it's partially masked by the confounding influence of genetics. This mirrors real-world situations where multiple factors interact in complex ways, and the idea is to untangle these relationships to discover what truly causes what.

When Hume wrote about "constant conjunction," he was describing what we now call correlation. We observe that certain events tend to occur together, and our minds naturally form expectations based on these patterns.

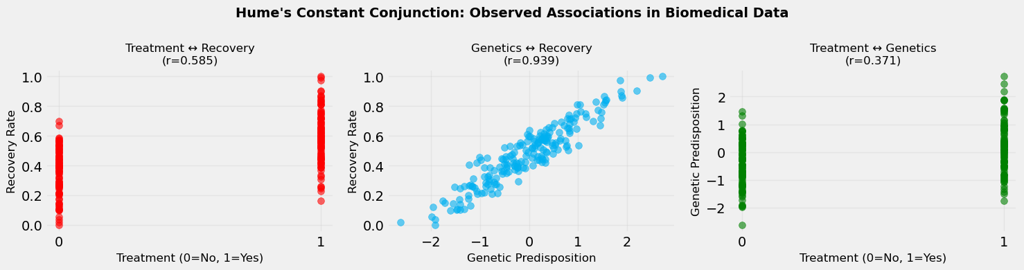

In our biomedical example, we observe strong correlations between:

These correlations are real, they exist in the data. But here's where Hume's insight becomes crucial: observing that two things occur together doesn't tell us whether one causes the other, or whether they're both caused by something else entirely.

This is the fundamental challenge of causal inference. We can measure correlations with precision, but correlations alone cannot answer causal questions. We need something more, we need to understand the underlying causal structure, to control for confounders, and to think in terms of counterfactuals.

The numbers we see in Figure 1 above, the correlation coefficients, are seductive in their clarity. But as we'll discover, they can be misleading guides to understanding what truly causes what.

Imagine you're a data scientist tasked with evaluating this new drug. You have data on thousands of patients: some received treatment, some didn't. You want to know: Does the treatment work?

The most straightforward approach, what we might call "predictive modelling" or "naive analysis", would be to simply compare recovery rates between treated and untreated patients. Fit a model, get a coefficient, report the result. Done.

But this approach has a fatal flaw: it assumes that the only difference between treated and untreated patients is the treatment itself. In reality, treated and untreated patients might differ in many ways; age, genetics, socioeconomic status, disease severity, and countless other factors.

When these other factors (confounders) influence both treatment assignment and recovery, the naive model will give you a biased estimate. It will mix together:

The result? You might conclude the drug works when it doesn't, or that it doesn't work when it does. In medicine, such mistakes can be literally a matter of life and death.

This is why we need causal models that explicitly account for confounders. By controlling for genetic predisposition (or other confounders), we can isolate the true treatment effect from the spurious associations.

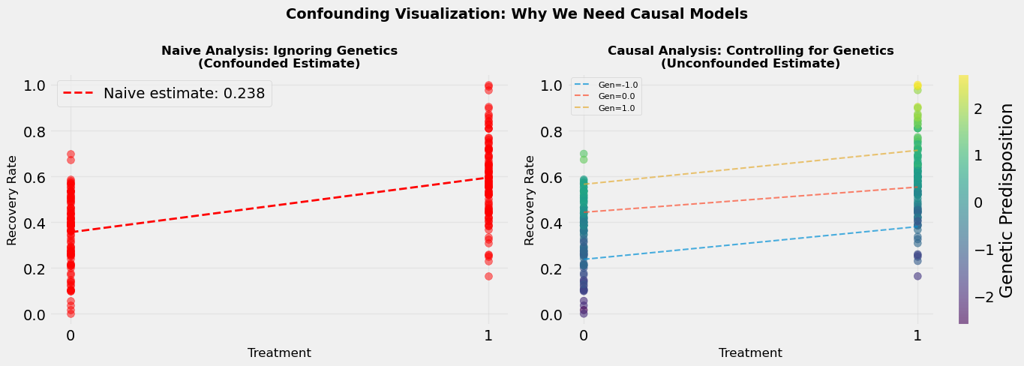

When we look at the data without controlling for genetics, we see one picture: treatment and recovery are strongly associated.

Figure 2 shows the outcome of a Naive Analysis (Predictive Modeling Approach), where

Estimated treatment effect: 0.238 which means Treatment increases recovery by 23.8%

But this picture is distorted by the confounding influence of genetics.

When we control for genetics, when we compare treated and untreated patients within the same genetic group, we see a different picture.

Figure 2 (right) shows the outcome of a Correct Analysis (Causal Modeling Approach), where

True treatment effect: 0.112 which means Treatment increases recovery by 11.2% after controlling for genetics

The treatment effect becomes clearer, more accurate. We're no longer comparing apples to oranges; we're comparing like to like.

This is the fundamental principle of causal inference: to identify causal effects, we need to make fair comparisons. We need to compare what would happen to the same person (or similar people) under different treatment conditions. Controlling for confounders helps us create these fair comparisons.

The visualisation shows this dramatically. On one side (Figure 2, left), we see the naive analysis, the confounded estimate that mixes treatment and genetic effects. On the other side (Figure 2, right), we see the causal analysis, the un-confounded estimate that isolates the true treatment effect by looking within genetic groups.

The difference between these two estimates is the confounding bias, the error we make when we ignore confounders. In real-world applications, this bias can be substantial, leading to incorrect conclusions and poor decisions.

Here's a thought experiment that gets to the heart of causal inference:

Imagine a patient named Sarah. She received the treatment and recovered. The question: Did the treatment cause her recovery?

To answer this, we would need to know: What would have happened to Sarah if she had NOT received the treatment? If she would have recovered anyway, then the treatment didn't cause her recovery. If she would not have recovered, then the treatment did cause it.

But here's the problem: we can never observe this counterfactual. Sarah either received treatment or she didn't. We can't go back in time and run the experiment again with the opposite treatment. We can't observe both the factual outcome (what happened) and the counterfactual outcome (what would have happened) for the same person.

This is what statisticians call "the fundamental problem of causal inference." We can observe correlations, but we can never directly observe causation because causation requires comparing what happened to what would have happened—and we can only observe one of these.

Yet, somehow, we do make causal claims. We do believe that treatments cause recoveries, that smoking causes cancer, that education causes better outcomes. How is this possible?

The answer lies in causal inference methods. By making assumptions (about exchangeability, positivity, and consistency), by using randomisation, by controlling for confounders, and by leveraging natural experiments, we can estimate what we cannot observe. We can infer counterfactuals from factual data.

This is the magic of causal inference: it allows us to answer "what if" questions even though we can only observe "what is."

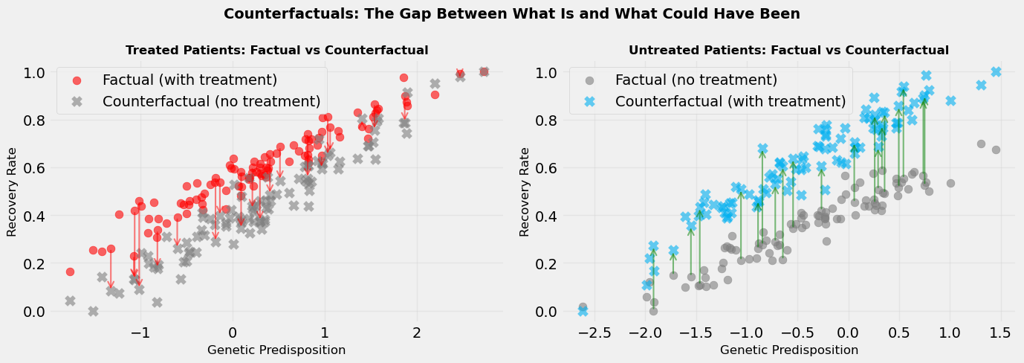

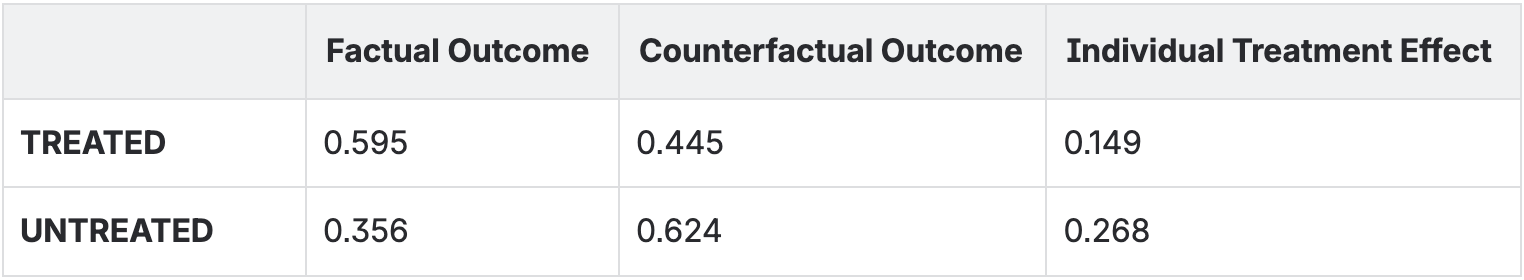

Counterfactuals are, by definition, unobservable. But we can visualise them conceptually. In Figure 3, we show:

For treated patients, the counterfactual is: what if they hadn't been treated?

For untreated patients, the counterfactual is: what if they had been treated?

The difference between factual and counterfactual outcomes is the individual treatment effect, the causal effect of treatment for each specific person. This effect can vary from person to person (treatment effect heterogeneity), which is why some patients benefit more from treatment than others.

When we average these individual treatment effects across all patients, we get the average treatment effect (ATE), the overall causal effect of treatment in the population.

Average Treatment Effect: 0.207

The visualisation shows this dramatically. We see arrows connecting factual to counterfactual outcomes. The length of these arrows represents the treatment effect. Some arrows are long (large treatment effect), some are short (small treatment effect). This heterogeneity is real and important, it tells us that treatment doesn't affect everyone the same way.

Understanding counterfactuals is essential for causal reasoning. It's what allows us to move from "treatment and recovery are correlated" to "treatment causes recovery." It's the bridge between observation and causation.

Let's step back and ask a fundamental question: Why do we care about causation at all? Why isn't prediction enough?

The answer lies in what we want to do with our models, not just what we want to know.

Predictive models are incredibly powerful. They can forecast stock prices, predict customer behavior, identify fraud, and diagnose diseases. They answer the question: "What will happen?"

But prediction has limits:

Causal models answer a different question: "What will happen if I intervene?"

This is crucial because:

Imagine a new patient arrives at the hospital. They have a genetic predisposition score of 0.5. Should we treat them?

A predictive model would say: "Based on past patients with similar characteristics, this patient has a 75% chance of recovery if treated and 60% if not treated. Therefore, treat them."

But this prediction might be confounded. The model might be using the correlation between treatment and recovery, which includes both the true treatment effect and the genetic effect. The recommendation might be wrong.

A causal model would say: "After controlling for this patient's genetics, the true causal effect of treatment is to increase recovery probability by 15 percentage points. Therefore, treat them."

The causal model's recommendation is based on understanding the true mechanism, not just patterns in the data. It's more reliable because it separates causation from correlation.

In medicine, the stakes are high. Recommending the wrong treatment can harm patients. Approving ineffective drugs wastes resources and delays finding effective treatments. Missing effective treatments costs lives.

This is why causal inference isn't just an academic exercise—it's a practical necessity. We need to know not just what's correlated with what, but what causes what. We need to understand not just patterns, but mechanisms.

Hume's philosophical insight from 300 years ago remains profoundly relevant: we can only observe associations, but we need to understand causes. Causal inference is the bridge between what we can observe and what we need to know.